The Moment of Encounter: In Conversation with Tina Campt

Screenshot from lecture Prelude to a New Black Gaze by Tina Campt at Studium Generale Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam.

This week we had the pleasure of being in dialogue with an author and thinker who has greatly influenced contemporary readings around photography – feeling through and theorising image cultures. Tina Campt is a Professor of Humanities and Modern Culture and Media at Brown University where she leads the Black Visualities Initiative. Her pioneering work generates new discourse around gender, racial, and diasporic formations in black communities, focusing on the role of ‘vernacular photography’ in processes of historical interpretation. Some of her notable publications include: Other Germans: Black Germans and the Politics of Race, Gender and Memory in the Third Reich (University Michigan Press, 2004); Image Matters: Archive, Photography and the African Diaspora in Europe (Duke University Press, 2012); and more recently, Listening to Images (Duke University Press, 2017).

Tina Campt interviewed by Rahaab Allana and Anisha Baid

In this interview, we spoke extendedly about her most recent book, Listening to Images which presents an intuitive, investigate and moving argument for an embodied, sensorially engaged way of understanding photographs and the stories which they can tell. Developing from Campt’s research and writing about identification photography from African diasporic communities, we step into the contemporary moment wherein the very idea of migration is used as a metaphor for both, being at home, and being alienated from it.

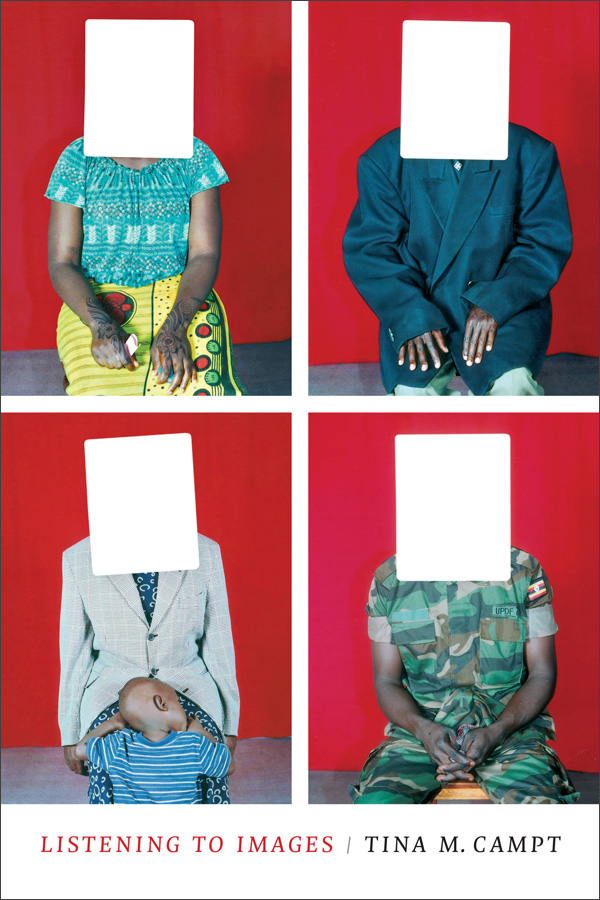

Listening to Images by Tina M. Campt, Book Cover, Duke University Press

Campt talks about developing her own methodology – taking on the role of an anthropologist, an art historian, a community worker, a professor – in order to illuminate the lives of South African diasporas. She describes how one of her leading impetus’ for doing so was to undo and diversify stereotypes or familiar projections when encountering photographs of that community (or any community). When writing about images, she says that as a practice, she would sometimes engage in the act of remembering and the emotive manifestations of recall, by thinking about what she saw. That very moment created a new form of exchange through the activation of memory, imagination and free association.

I wanted to find a way for accounting for feelings… for affective responses, for being moved by images in different ways that were not about the person who was in the photograph… or the scene that was being accounted for.

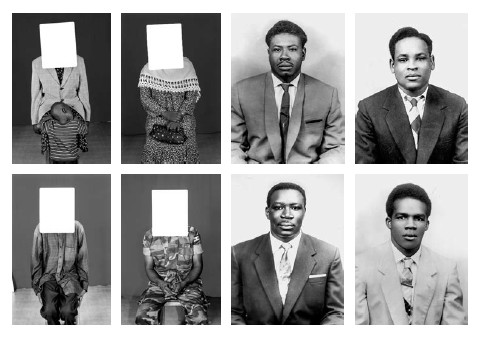

From the book Listening to Images (p. 44) | The Ernest Dyche Collection, Birmingham City Library, ms 2912. Martina Bacigalupo, Gulu Real Art Studio, 2011–2012. Courtesy the artist and The Walther Collection.

In the book Listening to Images, Campt discusses how genres of photography do not necessarily provide insight into social conditions or formations, such as histories of migration, structures of colonialism and the straightjacketing of identity creation. This becomes overtly clear, even when we look at passport photographs used in travel documents and work portfolios, as well as mugshots of incarcerated peoples. Such a publication then reminds us of another one titled Passport Photos by Amitava Kumar (University of Chicago Press, 2000), that has been described as: A multigenre book combining theory, poetry, cultural criticism, and photography, [as] it explores the complexities of the immigration experience, intervening in the impersonal language of the state. Passport Photos joins books by writers like Edward Said and Trinh T. Minh-ha in the search for a new poetics and politics of diaspora.

Diving into “official” archives, Campt insists that they may not be seen as purely instrumental artefacts, and goes on to explore their status as precious mementos that appear in family archives – those images of implicit refusal and/or the quiet reclamation of identity through keepsakes. In doing so, she places these archives in networks of overlapping and disparate memories, looking at them as image-making practices which have a social life beyond the intention of the photographer, the subject or even the collector.

I wanted to understand what motivated people to take an image, to share an image, to keep an image, to use an image, to cherish an image… all of those things.

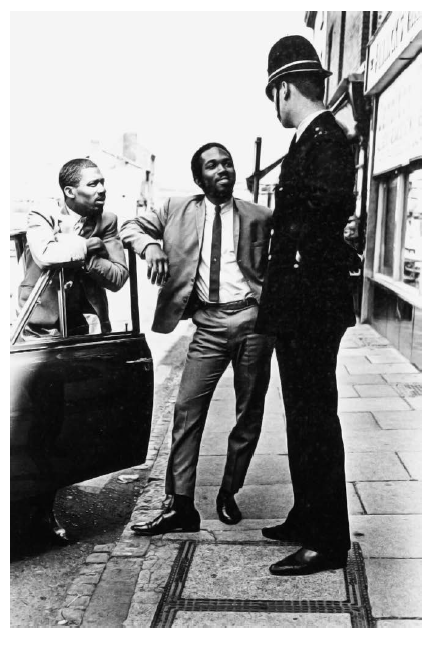

From the book Listening to Images (p. 35) |Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham.

Discussing her interests further in vernacular photography, Campt highlights the origins of the notion of ‘vernacular’ for her as being situated in everyday practices. Vernacular photography then, is not simply a genre, not only a technical or formal concern, but one that encompasses a whole social, political and sensorial network within which these media practices may be broadly considered.

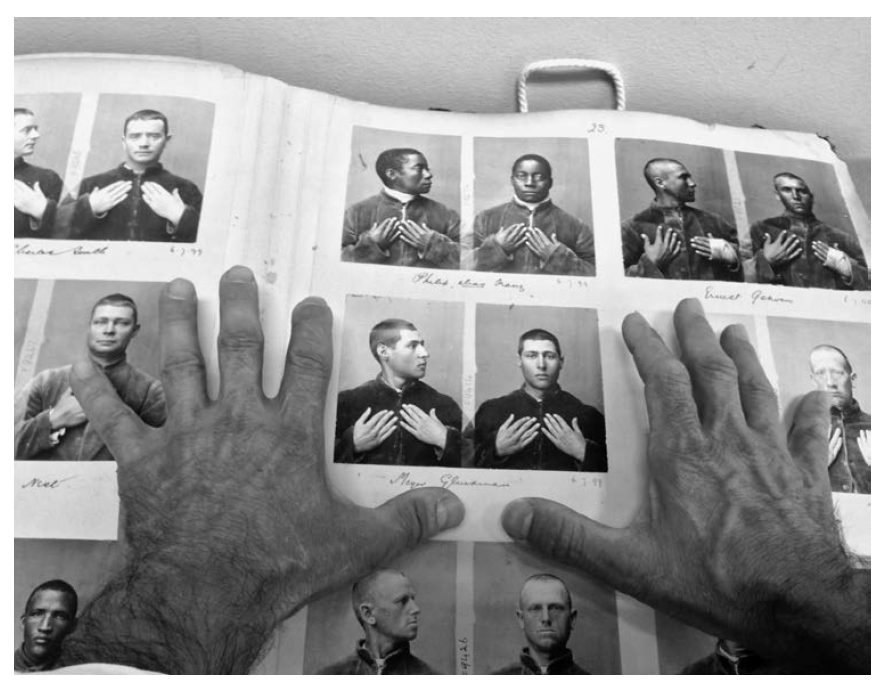

From the book Listening to Images (p. 99) | Courtesy of the Western Cape Archives and Records Service.

Discussing specifically her interactions with communities from the West Indies in Birmingham (England), Campt talks about the multiple moments of exchange and deliberation that a photograph potentially contains and invites. In her other book, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe (2012), Campt describes how these photographs conveyed profound aspirations around forms of national and cultural belonging. Placing special emphasis on the tactile and sonic registers of family photographs, she uses them to read into the complexities of situatedness as well as considerations of race – not only as micro-histories but as resonating signifiers, each with its own peculiar life-world that is embedded with implicit stances of departure – that further prompts a community to reject the supposed limitations of a subject position.

Looking at vernacular photography… as an everyday practice allows us to account for folks who get overlooked and speak to those individuals who are not exceptional. It allows us to really be able look at practices that aren’t understood as legible or representative.

From the book Listening to Images (p. 110) | Tumblr collection of images

Eventually responding to the question of pedagogy, and its relationship with arts or media practices, Campt astutely calls upon the contemporary moment in America, where the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement has catalysed well beyond one location, one incident or one meaning. She remarks on the dialectic and dialogic nature of the relationship between the pedagogical and performative assertions of the BLM movement, and the years of research and scrutiny that have a undeniable bearing this moment. Placing faith in the younger generation, now at the forefront of Black Lives Matter, as well as Abolition movements, there is now an intensified call to end police brutality and mass incarceration in the United States. Campt emphasises that continual assessment, refreshed probing and study can not only give rise to, but emerge from a transformative pedagogy – that very moment of encounter.

Comments